The study, under investigation by its publisher, has fueled a dispute over the age of a partially excavated site and prompted warnings about the dangers of nationalist mythmaking.

In a mountainous corner of Indonesia lies a hill, dotted with stone terraces, where people come from around the country to hold Islamic and Hindu rituals. Some say the site has a mystical air, or even that it might hold buried treasure.

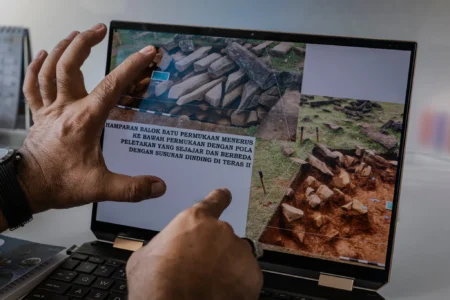

The partially excavated site, Gunung Padang, is a relaxing place to spend an afternoon. It’s also at the center of a raging debate.

Archaeologists say that the hill is a dormant volcano and that ceramics recovered there so far suggest that humans have been using the site for several hundred years or more. But some Indonesians, including an earthquake geologist and a president who left office in 2014, have suggested that the site may have been built far earlier by an as-yet-undiscovered ancient civilization. Their narrative has spread for more than a decade within the country but not very far beyond it — until recently.

In 2022, a Netflix documentary series, “Ancient Apocalypse,” drew on the geologist’s research for an episode about Gunung Padang. And in October, the geologist published an article in an international scientific journal that has fueled an international dispute over questions of science, ethics and ancient history.

Archaeologists say the study’s most contentious conclusion — that Gunung Padang may be “the oldest pyramid in the world” because its deepest layer appears to have been “sculpted” by humans up to 27,000 years ago — is problematic because it is not based on physical evidence. Indonesia had no history of pyramid construction, they say, and humans in the Paleolithic era, which ended more than 10,000 years ago, could not have constructed pyramids. (The pyramids of Giza in Egypt are only about 4,500 years old.)

The study’s New Jersey-based publisher says it is now conducting an internal investigation, meaning that the journal is “examining concerns shared by the archaeological community.” Several archaeologists have aired their concerns publicly, saying the study is “not worthy of publication” and that the geologist’s claim that the hill was built by humans “just doesn’t make sense.”

In response, the study’s lead author, the earthquake geologist Danny Hilman Natawidjaja, says it has been misunderstood. His supporters include Graham Hancock, the British journalist who starred in the Netflix series and has argued — to his own critics — that archaeologists should be more open to theories that challenge academic orthodoxy.

“This judge-jury-and-executioner model of archaeology, where they can define what is and what is not evidence — what is and is not acceptable as evidence — isn’t helpful in the long term for the progress of human knowledge,” Mr. Hancock said in a telephone interview.

Gold in that hill?

Gunung Padang lies near the city of Bandung on Java, Indonesia’s most populous island. Excavation began in the early 1980s, said Lutfi Yondri, an archaeologist with the Bandung provincial government.

Young Indonesians inspired by quixotic efforts to discover lost pyramids in Bosnia later promoted the idea that pointy hills could be hiding lost pyramids, Mr. Lutfi said. President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono’s staff organized forums to explore that question, as well as unproven speculation that Gunung Padang might contain buried treasure.

Archaeologists pushed back from the start. But Mr. Yudhoyono’s administration continued to finance excavation work at Gunung Padang, and he said after visiting in 2014, near the end of his 10-year term in office, that it could be “the largest prehistoric building in the world.”

The pyramid narrative “has some nationalistic edge to it, and it’s backed by a former president,” said Noel Hidalgo Tan, an archaeologist at the Southeast Asian Regional Center for Archaeology and Fine Arts in Bangkok.

“That’s why it’s a myth that refuses to die,” he said.

Mr. Yudhoyono’s assistant referred questions to Andi Arief, who once organized forums about Gunung Padang as a member of the president’s staff. Mr. Arief responded to an inquiry but did not make himself available for an interview.

Science or illusion?

Mr. Natawidjaja, the geologist who led the October study, said that he began researching the site in 2011. At the time, he was studying an active fault in the area and noticed that Gunung Padang’s pointy shape made it stand out in a landscape of eroded hillsides.

President Joko Widodo cut off financing for the research after assuming office in 2014. Mr. Natawidjaja later published his findings in a recent edition of Archaeological Prospection. The study’s methods and principles are the same ones that he would use to analyze earthquakes, he said in a Zoom interview.

“I’m just changing the subject from active faults to pyramids,” he said.

Several archaeologists said the study’s major problem is that it dated the human presence at Gunung Padang based on radiocarbon measurements of soil from drilling samples — not of artifacts recovered from the site.

“The lesson is that radiocarbon dates are not magic, and have important caveats around their interpretation,” the archaeologist Rebecca Bradley wrote in a 2016 critique of Mr. Natawidjaja’s preliminary findings. (She said in an email that his recently published study struck her as “a more organized recapitulation of the same old stuff.”)

Mr. Tan, the archaeologist in Bangkok, described the study’s attempt to link the soil’s age to human activity as its “biggest logical fallacy.” The soil’s age is not surprising because soil accumulates over time and deeper layers tend to be older, he added. “But it’s not soil that is tied to construction activity. It’s not soil that’s tied to, say, a fire pit, or soil that’s tied to a burial.”

“It’s just soil,” he said.

Ceramics and other evidence from the upper layers of Gunung Padang indicates that humans were there as early as the 12th or 13th centuries, and that they built structures atop natural rock formations, said Mai Lin Tjoa-Bonatz, an archaeologist who has conducted research in Indonesia.

“There could have been some people before, but they didn’t leave anything that we can date, so far,” said Professor Tjoa-Bonatz, who teaches at Humboldt University in Berlin.

Harry Truman Simanjuntak, an Indonesian archaeologist, said he also saw the study’s pyramid claim as unsubstantiated.

“There are always scientists who are illusionists and practice pseudoscience, seeking knowledge that is not based on data,” he said.